Cabbing it up

In the modern world, presentation and packaging is absolutely central to how we experience (and sell) everything. When videogame arcades tried to break that rule, it almost led them to disaster.

If you went to a shop to buy the latest blockbuster videogame, handed over your £50 and were given in return a blank unboxed disc with the name scrawled on it in marker pen, you’d be really unhappy about it – even though the disc would contain the exact same game code and play exactly the way it does when it comes in a pretty case.

It’d be like ordering a cup of tea in a cafe and have them bring you a cup of cold water, a teabag and a kettle – you’ve technically got everything that you need, but it’s not the experience you were hoping for.

And yet, for many years – and to some extent even today – that’s exactly the way we treated arcade games.

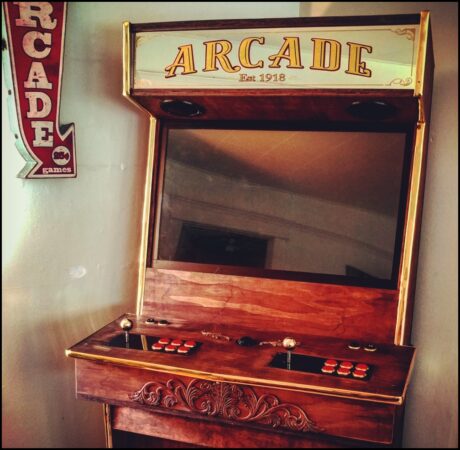

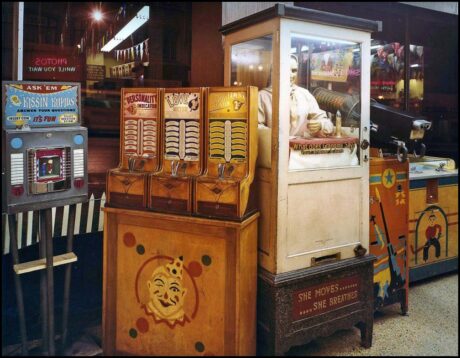

The first ever arcade games, in the 1950s and 60s, were electromechanical, so they needed to come in dedicated physical cabinets because there was no other means of interacting with the game. As such the cabinet itself – not a screen or a speaker – had to do all the work of attracting passing players.

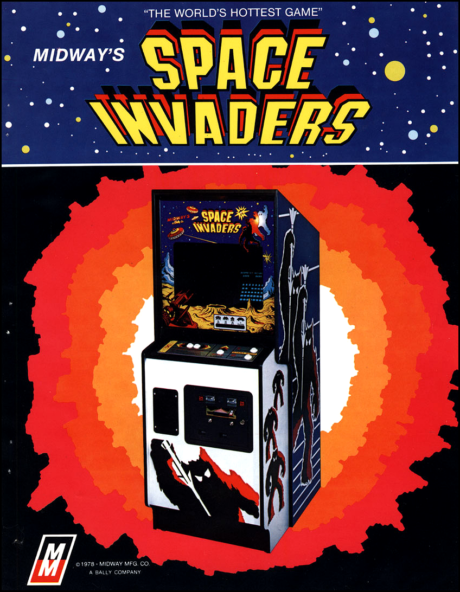

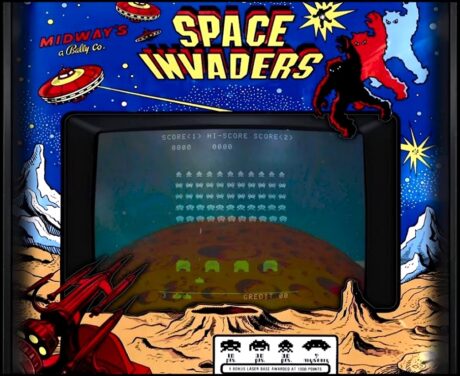

When all-electronic videogames were invented in the mid-1970s, they naturally carried on in that tradition. The flyer for the original Space Invaders takes artwork that was already pretty loud – huge, dark golems clutching massive missiles as they stomp across a lunar landscape ahead of waves of classic 50s-style UFOs – and blows it out of a series of garish concentric explosion shockwaves that look like they were painted by an over-excited child.

Almost every inch of the cabinet is packed with action aimed at luring in gamers, from the marquee and the kickplate to the evocative control panel imitating (on the original Japanese machine) a spacefighter cockpit.

Even the screen part is doubly ornamented, first with the cartoonish “bezel” surround and then with the subtle painted backdrop onto which the Invaders are projected.

(Unusually, in Space Invaders you’re not actually looking at the screen itself, but at a reflection of it – the actual monitor is black-and-white, the image fired through coloured strips of cellophane onto the painted backdrop to give it a double illusion of colour on the cheap. Monochrome displays didn’t survive in arcades much past Invaders’ debut in 1978.)

The mad electronic goldrush of the next few years was ironically enough a bountiful time for old-fashioned artists. With arcades springing up everywhere and an insatiable appetite for new games, but the technology still very limited in what it could depict onscreen, it was chiefly the job of sketchers and painters to portray these exotic new vistas through spectacular cabinet art.

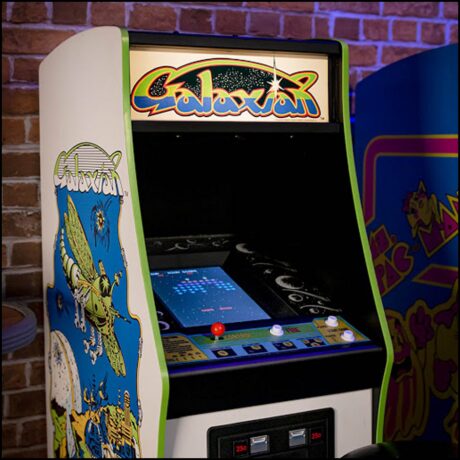

But there was more to it. The physical design of the units and the controls had a role to play too. One of the most iconic cabinets of all time is the early Namco model used for games like Pac-Man, Galaxian and Rally X. Rather than having its screen at head height, facing the player, it’s recessed deep within the cabinet at a low angle so they need to look down from above to play.

This was probably a pragmatic economic choice as much as an artistic one – a lower, flatter screen is playable by a wider range of player ages and heights. But the effect is to draw the player into the game’s world, shutting out the other sights and sounds of the arcade and focusing their senses on the fantasy environment, as if they’d stuck their head into the wardrobe leading to Narnia.

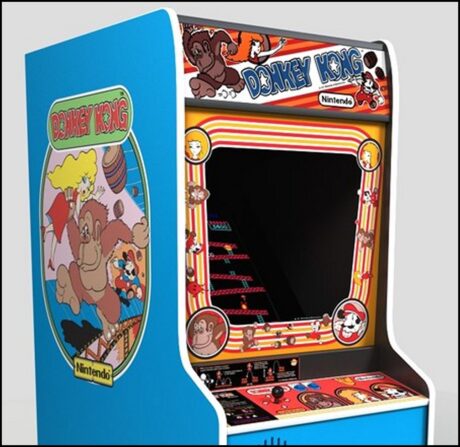

(Nintendo games like Donkey Kong and Popeye used a similar approach, with another recessed screen this time placed behind a glass front panel, creating the impression of looking through a window or at a theatrical stage – with the bezel art as the “curtains” in both cases, presumably.)

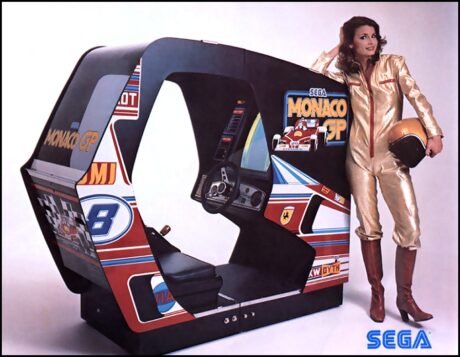

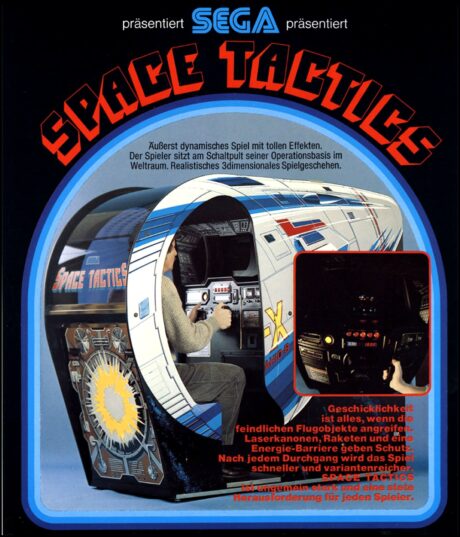

Special “cockpit” cabinets – most commonly deployed for mass-appeal racing games like Monaco GP, Turbo and Pole Position – took the immersive principle a step further, enclosing and seating the player in a protective cocoon to simulate the feeling of being in a racing car, or at the complex controls of an intergalactic spaceship, as with Sega’s elaborate Space Tactics.

But as always, commercial pressures soon started to kill the magic. Dedicated cabinets were expensive, running arcade operators thousands of pounds each, and few games could earn enough at 10p or 20p a play to recoup that sort of outlay before novelty-hungry players moved on to the next hot title (especially as skilled players could make a single credit last for hours), leaving owners stuck with a bulky inventory of duffers and old news, useful only as firewood and spare-parts salvage.

So some enterprising sorts started designing “generic” cabinets (common examples in Europe included the Brent Leisure BAS model, the Silverline and the AMR), into which the guts of new games could be transferred with relative ease. What had been a Donkey Kong one week might be a Scramble the next time you turned up at the arcade, despite outwardly appearing to be the same machine.

The invention of the JAMMA wiring standard by the Japanese arcade industry in 1985 formalised this practice and really signed the death warrant for the dedicated standup cabinet. Now every game was just a motherboard of ROM chips designed to be slotted in and out of a cabinet with ease.

Standard cabinets meant standard stick-and-buttons controls, so anything innovative became uneconomic and impractical. The torrential flow of exciting new ideas that typified the “wild west” years of the late 70s and especially the early 80s dried up to a handful of genres – mainly scrolling shooters, fighting games and sports sims designed for use in these homogenised cabinets.

(The phenomenon probably peaked with the introduction in 1990 of the Neo Geo MVS, which was an entire system specifically designed from the outset around the principle of interchangeable innards.)

It’s not that there was anything wrong with the games of this new age – many were wonderful – but the magic of the experience, the sense of occasion engendered by the arrival of a brand new cabinet, was diminished greatly, a bit like watching a movie streaming to your iPhone’s 5-inch screen on the bus rather than at the Empire in Leicester Square.

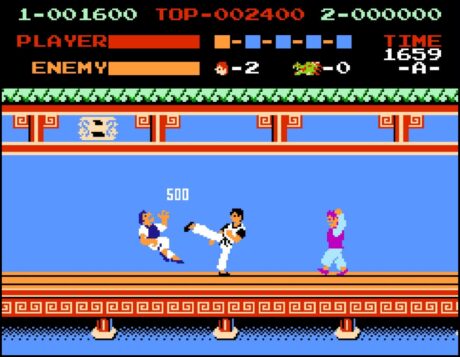

At the same time, home computers and consoles were beginning to rapidly close the technological gap on arcades. There was no comparison at all in 1982 between coin-op Pac-Man and the Atari VCS version, despite the home game arriving almost two years later, but you only had to squint your eyes a little bit when playing the 1985 NES port of Kung-Fu Master (below) to plausibly mistake it for the 1984 arcade original.

(There’s a whole other feature to be written about people who’ve gone back and created far better arcade ports on old hardware than they actually got at the time, including several vastly superior interpretations of Pac-Man on the VCS, but this is not that feature.)

So something had to be done to draw the crowds back to the amusement parlours. And the answer was to make cabinets special again.

Nothing had changed in the costs equation, so the bulk of the typical arcade would still be made up of generic JAMMA cabs (nowadays typified by the sleek white plastic “Astro City” and “Candy” models, especially in Japan).

But there would also be the new showstopping centrepiece attractions which definitely couldn’t be simulated in front of your home TV. From the mid-80s onwards, cockpits were back in a big way.

The unchallenged pioneers in this new wave were Sega. With money to burn from a number of big arcade hits (with lots of licenced conversions) like Zaxxon, Frogger, Congo Bongo and Buck Rogers, and their own home consoles like the Master System, they invested on titles that made arcades an event destination again, and would become iconic in their own rights.

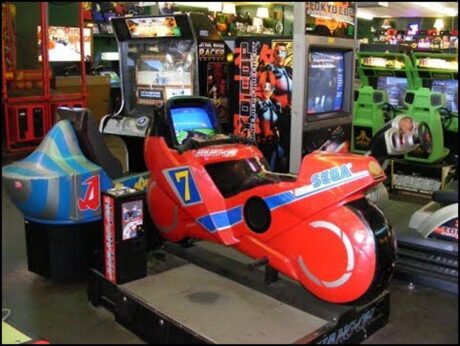

The first salvo was 1985’s Hang-On, a fast and slick but in truth pretty mundane track racer elevated by the life-size motorbike the player was invited to sit astride to play it. The package may have prioritised style and control innovation over content, with 3D graphics disguising extremely one-dimensional gameplay, but it achieved those goals in spades. Nothing remotely like it had been seen in arcades before.

While successful, Hang-On wasn’t a universal hit – a 240kg pretend motorbike was a lot for younger or smaller gamers to throw around, and the game offered little reward for their exertion, just a sequence of sparse identikit tracks in which nothing much happened. So Sega’s next big-ticket show pony went in the opposite direction and offered up equal-opportunity thrills for everyone.

Space Harrier rightly remains one of the company’s most-loved classics. The futuristic, angular cabinet strapped players in – it actually came with a purely-cosmetic seatbelt – and took them for the ride of a lifetime through a spectacular fantasy world in which dragons, Easter Island heads and giant killer robots all lived side-by-side, hurling themselves headlong towards the captivated player across a speeding chequered landscape in dazzling blue-sky colours.

With powerful motors having pitched and rolled the entire ensemble around dramatically for the entire duration, first-time players would stagger off the machine breathless and weak at the knees (both from excitement, rather than exhaustion as with Hang-On). Space Harrier was a smash, and attracted ports for just about every home format imaginable because even without the gimmick the underlying game was fun. Sega got the best of both worlds – a hit home game that still gave people a reason to go to the arcades for a whole extra level of enjoyment.

But what it really did was open the floodgates for the idea of physical (or “taikan”, translating to “bodily sensation”) arcade games. Sega themselves would make many more, famously including Out Run, Thunder Blade, After Burner and Power Drift and culminating in the terrifying all-axis-spinning R-360 cabinet hosting G-LOC: Air Battle, but other companies also picked up the ball and ran with it to great effect.

Namco were particularly enthusiastic adopters, with titles as diverse as Prop Cycle, Alpine Racer and Final Furlong, culminating in arguably the creative pinnacle of the form – Ridge Racer Full Scale, in which the player sat in a real-life Mazda MX-5 sports convertible (with working dials and air blowing through the vents) in front of a giant super-wide screen.

(Indeed, the environment was SO realistic that it slightly backfired – the car didn’t move, and having your eyes telling you you were pulling off a daring high-speed drift around a spectacular mountain racetrack in a real car while all your other senses insisted that you were in fact totally stationary was disorientating and could ironically trigger a feeling of motion sickness.)

Konami, meanwhile, gave arcade-goers serious workouts with high-activity games like the exhausting, motion-sensing Police 24/7 (in which you basically had to mime your way through a particularly energetic episode of Starsky And Hutch, ducking behind cover and dodging bullets by moving your body, not a joystick) and the phenomenon that was Dance Dance Revolution, in which not only the cabinet itself but also the player’s performance became a spectator attraction.

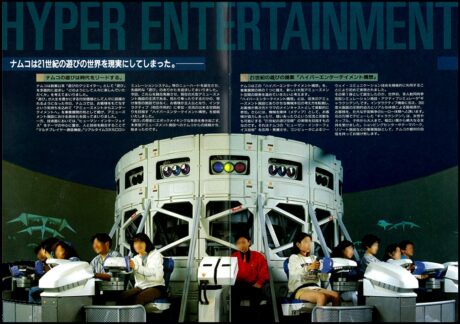

The next step – and a logical progression – was to turn those spectators into paying participants, so everything scaled up again with truly gigantic cabinets that could only fit into the most cavernous of dedicated arcades. Namco’s epic co-operative space opera Galaxian 3 seated six pilots in its most compact incarnation – still a chunky 17 feet by 8 feet – but a special version for a Japanese trade exhibition catered for a staggering 28 players in a custom-built circular room with the game projected on the walls and a hydraulic motion unit shifting the whole construction around.

But the most successful multi-cockpit games were those that went back to the genesis of the sit-down format: the racers. And while Ridge Racer, Out Run and Virtua Racing all had multi-seat iterations, the daddy of them all was another Sega flagship – Daytona USA, which pitted up to EIGHT friends and strangers against each other at once in races guaranteed to be over in a couple of minutes, leaving the machines free for the next group of eager and full-pocketed punters. (Or indeed, the same ones keen for a rematch.)

The old problem had been solved. By going full-circle back to dedicated cabinets offering a unique and lavishly-presented experience, arcades had reinvented and saved themselves, carving out a niche somewhere between the old walls of standup cabs and a theme park. (But indoors safe from the weather, and without all the hassle of travelling halfway across the country, coughing up a fortune for admission and spending most of your day queueing.)

It was undoubtedly Sega who led the rescue, with what became and are still some of their most famous brands, but an entire industry that had almost killed itself with greedy plain-packaging cheapskatery saw which way the wind was blowing and jumped on the bandwagon just in time with a cabinet of curiosities made up of countless curious cabinets.

The just-in-time return of dedicated cabs gave the arcades a second golden age, as well as paving the way for home innovations like the Wii and Guitar Hero. Let’s give them a standing (or sitting or spinning around, as appropriate) ovation.

.

Special thanks to Darren Wall at the splendid Read-Only Memory regarding this article.

Some of my best memory’s of being a kid was sitting on my dads lap playing full scale Out Run because i couldn’t reach the peddles.Space Harrier and Afterburner full size i could just manage.

The reason I’ve owned two MX5 MK1’s is because of Ridge racer full scale.Man i miss Codona’s in the 80’s and 90’s :(

you ever get the chance to see Sega’s holographic cowboy game cabinet? Tried explaining to so many people that holographic games had already been a thing years ago but no one ever believed me.

Great read Stu.

I always found those big Sega arcade machines to be a bit intimidating at the time! When I was at an arcade, I just wanted my faves (Kung Fu Master, Rolling Thunder etc). I knew that if I got on a big machine, it’d likely be 50p for a couple of minutes fun at best.

And then when arcades transitioned in the ’90s, those single game old style cabs were all gun and it was mostly all gun games (Time Crisis 2, House of the Dead 2 being ever-present) and three/four player driving games.

There’s a place in Elephant and Castle called Four Quarters that I checked out last month that had a bunch of classics (Donkey Kong, Pac-Man, R-Type etc) and a full size Out Run though. Well worth a look.

Fun article!